In the previous essays, we discussed operators and the hierarchy of Topological spaces on which they may act. Now we will begin connecting fundamental concepts from linear algebra to operator theory to build deeper intuition. We will derive the Rank-Nullity Theorem and show how it connects naturally to the Fredholm index.

Assuming we have a linear map

between vector spaces and

. We introduce the following definitions:

- The subspace

is the domain of

, describing the set of all admissible inputs to

. In this context,

is the ambient space.

- The image (or range) of

is

, the set of all outputs achieved by

. The space

is the codomain.

- The kernel of

is

, the set of all inputs that map to the zero vector in

.

A Motivating Example

Consider the transformation:

defined by for

. Here,

,

and

.

Moreover, .

In this case, , and

, while

. The Rank-Nullity Theorem predicts:

where

and

.

One might ask why we do not simply take . We can, but then we should redefine the transformation. Namely, if

is defined such that

then . In exchange, the nullity increases by one (compared to the restricted-domain version), so the Rank-Nullity identity still holds.

Quotient Spaces

Before proving Rank-Nullity, recall that for a subspace , the quotient space is

and the standard result in linear algebra states:

.

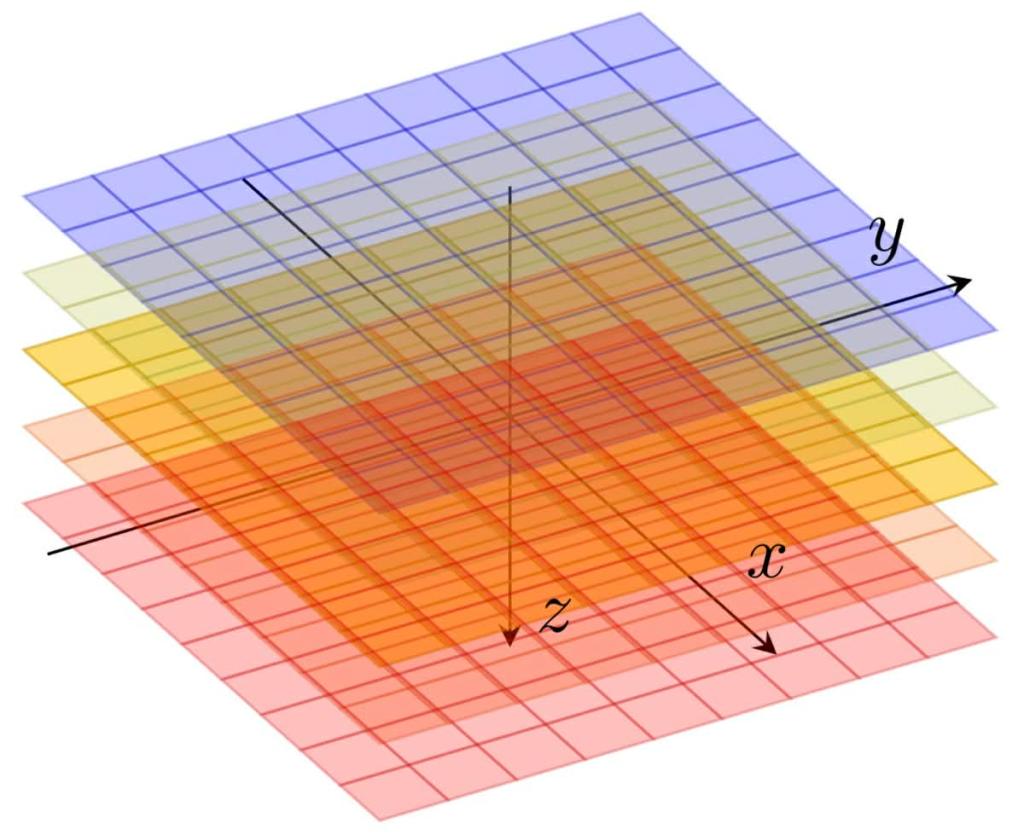

For example, in define

,

representing the x-y horizontal plane where .

Then , and we can form the quotient subspace:

which can be visualized as the family of horizontal layers parallel to .

Since , we get

.

Rank-Nullity Theorem (Proof)

Let

be a linear map. By linearity, is a vector-space homomorphism (i.e.

for all

), so by the First Isomorphism Theorem,

and more importantly,

rearranging this equation, one has

This is the Rank-Nullity theorem. Q.E.D.

The Fredholm Operator and Index

Now we should ask what proof of the rank-nullity theorem means for Operator Theory? Especially for operators where and

may be infinite?

Again consider

When dimensions are finite, we have

.

Substituting yields

and by rearrangement,

In infinite -dimensional settings, the left-hand side may be meaningless (as “” is not well-defined), while the right-hand side can still be finite. This motivates the following.

A bounded linear operator between Banach spaces

and

is called Fredholm if both

and

are finite. In that case we define the Fredholm index by

To interpret this, let denote the space of bounded linear operators from

and

, and define

and

One can show that . Indeed if

is invertible, then it is bijective (i.e. it is one-to-one and onto): injectivity implies

and surjectivity implies

. Hence,

and

.

Therefore,

The class is often described informally as the class of near-invertible operators: operators which become invertible after a “small” perturbation (in operator norm). We will not develop this theory here; readers can consult Harold Widom’s Pertubing Fredholm Operators to Obtain Invertible Operators for more detail.