During the course, my instructors emphasized discretion regarding the syllabus and post-graduation details. As a result, my Operation Gradient blog posts will not delve into the specific course structure or provide a comprehensive summary of everything covered. Instead, these blog posts will form a coup d’œil (or glimpse) referring to shared moments of inspiration, memorable experiences, and key insights, merged with some mathematical intuition.

In Part I, I shared details about my decision to journey the rigorous Officers’ course and the financial hurdles preceding it. Now, as we turn a bit closer to my time at Keesler AFB, let me begin with a question: what is a gradient?

In Part II, you will gain a deeply intuitive understanding of the mathematical concept of a gradient — what it is, how it works, and why it matters. However this won’t be a full technical discussion; gradients have practical value in Operations Research, but carried some philosophical value throughout my time in the course. I hope to provide you with the same experience, and maybe inspire you to further look into the technical details when you’re ready.

MOUNT DENALI

The gradient is defined in many ways, but first lets detour roughly 3500 miles away from Keesler, and imagine you are climbing Mount McKinley (also called Denali) with Lonnie Dupre, who (as of 2015) was the first ever recorded solo climber to reach its summit:

Frost stubbornly clung to Dupre’s beard in the video, forming a frozen mask that betrayed that unforgivably piercing chill few dare to endure. He managed to accomplish this feat in just 25 days, carrying vibrantly colored gear that provided the only warmth in a terrain carved by ice and wind. Now suppose at any point before the summit, I ask the question:

“Which direction yields the steepest ascent?“

Surely you know where the point of steepest ascent is, not only because you can probably see it, but also because Lonnie’s there to help. You’d point your 8 foot long, cambered skis along the path that offers the swiftest increase in altitude if we moved in that direction. That direction, in mathematical terms, corresponds to the gradient … a vector that shows us not only which way is up, but also how sharply the terrain rises.

Gradients are ubiquitous mathematical tools with philosophical relevance. Abstractly, they point in the direction of steepest ascent and, as we will see later in my technical blog, are remarkably useful in many applications of Operations Research. That said, here’s a space-faring example of how gradients are applied.

LAGRANGE POINTS

Lets venture roughly 932,000 miles above the Earth’s surface, to the L2 Lagrange point, home to the James Webb Space Telescope. If you aren’t steeped in space lore, you might wonder what a Lagrange point actually is.

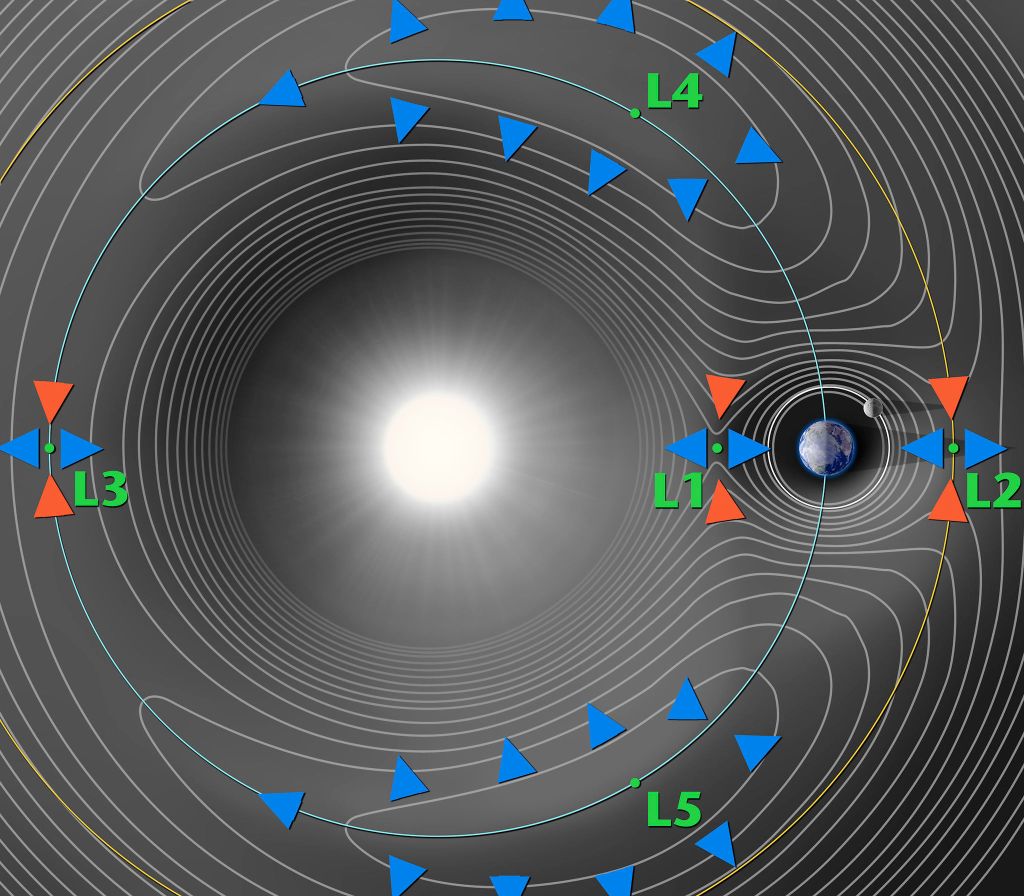

The image below portrays the effective potential field , i.e. the potential representing combined gravitational and centrifugal forces, between Earth and the Sun. Its contour lines represent regions where these forces share the same magnitude. Lagrange points (labeled L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5) are precisely those locations where the gradient of the effective potential vanishes (i.e. become zero).

This example is used to reveal how gradients can be used to uncover some insights that aren’t necessarily intuitive. Those five special locations in space appear empty, yet function like gravitational anchors, allowing spacecraft to orbit around them with minimal station-keeping. The graphic below further demonstrates the orbit of JWST around L2.

At this point, you likely understand that the gradient abstractly points in the direction of steepest ascent — whether it’s used to locate the summit (or peak) of Mt. McKinley or to determine the Lagrange points in an effective potential field. Hopefully my reason for titling these experiences “Operation Gradient” is as clear as verglas, but the central lesson from my 15A experience is that curiosity forms the landscape of great Operations Researchers, motivating us to reach its summits. Solving difficult problems often requires venturing into the related, seemingly esoteric fields, and at any point in this figurative landscape, it helps to know your gradient.

— Gecko

2 thoughts on “OPERATION GRADIENT: MY 15A EXPERIENCE (PART II)”